variable_name = 'variable_value'

first_name = 'Loki'

age = 10543 Core Concepts

In order to effectively use Python to interact with various datasets, we need to build out our fundamental knowledge about how Python works.

Adding tools to our Python toolkit

3.1 Variables & Assignment

We can assign values to variables in Python that we can use over and over. Variables are always assigned using the format:

Where the name of the variable is always to the left, and whatever value we wish to assign being on the right of =.

Some rules regarding naming variables:

- Names may only contain letters, digits, and underscores

- Are case sensitive

- Must not start with a digit

- Typically, variables starting with

_or__have special meaning, so we will try to stick to starting variables with letters only

- Typically, variables starting with

To display the value we have previously assigned to a variable, we can use the print function:

print(first_name, 'is', age, 'Earth years old.')Loki is 1054 Earth years old.Challenge 1

Challenge 2

If you noticed in the last challenge, you could go back to a previous cell above where you assigned a variable, and the print command would work. This is because, in a Jupyter notebook, it is the order of execution of cells that is important, not the order in which they appear. Python will remember all the code that was run previously, including any variables you have defined, irrespective of cell order.

After a long day of work and to prevent confusion, it can be helpful to use the Kernel → Restart & Run All option which clears the interpreter and runs everything from a clean slate going top to bottom.

3.2 Lists & Indexing

#sorrynotsorry R

Lists

An important aspect of Pythonic programming is the use of indicies to allow us to slice and dice our datasets. We will learn a bit more about indexing here through the introduction of lists. A list is an ordered list of items in Python, where the items can take on any datatype (even another list!). We create a list by putting values inside square brackets and separate items with commas:

my_list = [1, 'two', 3.0, True]

print(my_list)[1, 'two', 3.0, True]Indexing

To access the elements of a list we use indices, the numbered positions of elements in the list. These positions are numbered starting at 0, so the first element has an index of 0. Python has made it easy to count backwards as well: the last index can be accessed using index -1, the second last with -2 and so on.

If you have used other coding languages, such as R, you may notice that different programming languages start counting from different numbers. In R, you start your indexing from 1, but in Python it is 0. It’s important to keep this in mind!

print('First element:', my_list[0])

print('Last element:', my_list[-1])

print('Second last element:', my_list[2])

print('Also second last element:', my_list[-2])First element: 1

Last element: True

Second last element: 3.0

Also second last element: 3.0Strings also have indices, pointing to the character in each string. These work in the same way as lists.

print(first_name)

print(first_name[0])Loki

LHowever, there is one important difference between lists and strings: we can change values in a list, but we cannot change individual characters in a string. For example:

print(my_list)

my_list[0] = 'changing the first element!'

print(my_list)[1, 'two', 3.0, True]

['changing the first element!', 'two', 3.0, True]will work. However:

print(first_name)

first_name[0] = 'N'Loki--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[10], line 2 1 print(first_name) ----> 2 first_name[0] = 'N' TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

Will throw an error.

Data which can be modified in place is called mutable, while data which cannot be modified is called immutable. Strings and numbers are immutable. This does not mean that variables with string or number values are constants, but when we want to change the value of a string or number variable, we can only replace the old value with a completely new value.

Lists and arrays, on the other hand, are mutable: we can modify them after they have been created. We can change individual elements, append new elements, or reorder the whole list. For some operations, like sorting, we can choose whether to use a function that modifies the data in-place or a function that returns a modified copy and leaves the original unchanged.

Be careful when modifying data in-place. If two variables refer to the same list, and you modify the list value, it will change for both variables!

We can use indicies for more than just accessing single elements from an ordered object such as a list or a string. We can also slice our dataset to give us different portions of the list. We do this using the slice notation [start:stop], where start is the integer index of the first element we want and stop is the integer index of the element just after the last element we want. If either of start or stop is left out, it is assumed that you want to default with either starting from the beginning of the list or ending at the end.

number_list = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

print('0:5 --> ', number_list[0:5])

print('_:5 --> ', number_list[:5])

print('3:7 --> ', number_list[3:5])

print('3:_ --> ', number_list[3:])

print('3:-1 --> ', number_list[3:-1])0:5 --> [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

_:5 --> [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

3:7 --> [3, 4]

3:_ --> [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

3:-1 --> [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]We can also use a step-size to indicate how often we want to pick up an element of the list. By altering the slice notation to [start:stop:step] we will be telling the code to only include those elements at each step after start, ending at the final step that occurs just before running into stop. This allows us to reverse lists as well:

print('All evens:', number_list[0::2])

print('All odds: ', number_list[1::2])

print('Just 1 and 4:', number_list[1:5:3])

print('Reversed: ', number_list[-1::-1])All evens: [0, 2, 4, 6, 8]

All odds: [1, 3, 5, 7, 9]

Just 1 and 4: [1, 4]

Reversed: [9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]Challenge 3

Dictionaries

Another object that exists in Python is the dictionary. It is similar to a list in that it can hold a variety of different types of objects inside of it. However an important difference is in how we access these objects. With a list (or string), we have an ordered arrangement of items that we access with an integer index. However, we access the values in a dictionary with a key, which can be anything we want.

Let’s build a dictionary, which is denoted in Python with curly {} brackets:

my_dict = {

'first_key': 'some value',

'A': ['a', 'differerent', 'type', 'of', 'object'],

2: False

}

print(my_dict){'first_key': 'some value', 'A': ['a', 'differerent', 'type', 'of', 'object'], 2: False}Here we listed three key - value pairs. The key comes before the value, with a colon between. Commas separate different pairs. Now that we have a dictionary, we access it the same way as a list, with square [] brackets:

print(my_dict['first_key'])

print()

print(my_dict['A'])

print()

print(my_dict[2])some value

['a', 'differerent', 'type', 'of', 'object']

FalseUnlike a list, dictionaries are unordered, and so we cannot perform integer indexing or slicing of these elements:

my_dict[0]--------------------------------------------------------------------------- KeyError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[16], line 1 ----> 1 my_dict[0] KeyError: 0

my_dict[0:5]--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[17], line 1 ----> 1 my_dict[0:5] TypeError: unhashable type: 'slice'

Dictionaries are an abstract data type that can take a while to get used to! They can be a powerful tool in Python. Common uses for dictionaries include:

- Creating searchable parameter lists for models

- Supplying extra arguments to functions

- Storing complex outputs or datasets

We will not need to use dictionaries frequently in this course. However, they will become useful when we learn more about data tables and aggregation methods later on, and so gaining familiarity now is beneficial!

3.3 Data Types & Operations

Every value in a program has a specific type. In this course, you will run across four basic types in Python:

- Integer (

int): positive or negative whole numbers like 42 or 90210 - Floating point numbers (

float): real fractional numbers like 3.14159 or -87.6 - Character strings (

str): text written either in single or double quotes. - Boolean (

bool): the logical values ofTrueandFalse

If you are unsure what type anything is, we can use the built in function type. Note that this works on variables as well.

print(type(42))

print(type(3.14))

print(type('Otter'))

print(type(True))<class 'int'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'str'>

<class 'bool'>When you start to have really long integers, it starts to look really messy (how many thousands are in 1982137092 at a glance?) Luckily, Python allows us to use _ inside our integers to space out our digits. Thus we could write that instead as 1_902_137_092. Isn’t that nicer!

Basic Arithmetic

The type of a variable controls what operations can be performed on it. For example, we can subtract floats and ints, but we cannot subtract strings:

print(42-12)

print(3.14-15)

print('hello' - 'h')30

-11.86--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[19], line 3 1 print(42-12) 2 print(3.14-15) ----> 3 print('hello' - 'h') TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'str' and 'str'

However, we can add strings together:

my_sentence = 'Adding' + ' ' + 'strings' + ' ' + 'concatenates them.'

print(my_sentence)Adding strings concatenates them.As well as multipling a string by an integer to get a repeated string:

repeated_string = '=+'*10

print(repeated_string)=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+As we saw above, we can mix and match both of the numerical types, however we will get an error if we try to mix a string with a number:

print(1 + '2')--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[22], line 1 ----> 1 print(1 + '2') TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

In order to have a sensical operation, we need to convert variables to a common type before doing our operation. We can convert variables using the type name as a function.

print(1 + int('2'))

print(str(1) + '2')3

12Note that when converting floats to integers, it will always round down! That is, int(3.6) = int(3.1) = 3!

One last bit of math you might come across are the various types of division:

/performs regular floating-point division//performs integer floor division%returns the remainder of integer division

print('5 / 3 :', 5 / 3)

print('5 // 3:', 5 // 3)

print('5 % 3 :', 5 % 3)5 / 3 : 1.6666666666666667

5 // 3: 1

5 % 3 : 2Built in Functions

Python has multiple pre-built functions that come in handy. We have already made use of the print() command frequently, and learned how to use type() to tell us what type of data our variables are. Here are some other frequently used functions:

len(): Tells us the length of a list, string, or other ordered object. Does not work on numbers!help(): Gives help for other functionsmin(): Gives the mininum value in a list of options.max(): Gives the maximum value in a list of options.round(): Rounds a value to a given decimal length.

Note that, similar to the arithmetic operations above, these built in functions must operate on logically consistent datatypes. We can find the min of 2 strings, or 4 numbers, but we cannot compare a string to a float.

Every function in python will take 0 or more arguments that are passed to a function. For example, len() takes exactly one argument, and returns the length of that argument:

print(len('this string is how long?'))24Some functions, such as min() and max() take a variable number of arguments:

print(min(1,2,3,4))

print(max('a', 'b', 'c'))1

cWhile others have default values that do not need to be provided at all.

Challenge 4

In Jupyter notebooks, we can also get help by starting a line with ?. For example, ?round will display the help information about the round() function.

A Quick Intro to Boolean Logic

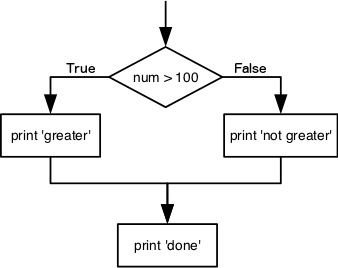

We can ask Python to take different actions, depending on a condition, with the if statement:

num = 37

if num > 100:

print('greater')

else:

print('not greater')

print('done')not greater

doneThe if keyword tells Python we want to make a choice. We then use : to end the conditional we would like to consider, and indentation to specify our if block of code that should execute if the condition is met. If the condition is not met, the body of the else block gets executed instead.

In either case, ‘done’ will always print as it is in neither indented block.

Following a Logical Flow

Conditional statements do not need to include an else block. If there is no block and the condition is False, Python simply does nothing:

num = 37

if num > 100:

print('greater')

print('done')doneWe can also chain several tests together using elif. Python will go through the code line by line, looking for a condition that is met. If no condition is met, it will execute the else block (or nothing if there is no else).

num = 45

if num < 42:

print('This is not the answer.')

elif num > 42:

print('This is also not the answer.')

else:

print('This is the answer to life, the universe, and everything.')This is also not the answer.There are multiple different comparisons we can make in Python:

>: greater than<: less than==: equal to (note the double ‘=’ here!)!=: does not equal>=: greater than or equal to<=: less than or equal to

And these can be used in conjunction with each other using the special keywords and, or, and not. and will evaluate to True if both parts are True, while or will evaluate to True if either side is. not will evaluate the condition, and then return the opposite result.

condition_1 = 1 > 0 # True

condition_2 = -1 > 0 # False

print('Testing and: ')

if condition_1 and condition_2:

print('both parts are true')

else:

print('at least one part is false')

print()

print('Testing or: ')

if condition_1 or condition_2:

print('at least one part is true')

else:

print('both parts are false')

print()

print('Testing not: ')

if not condition_1:

print('condition_1 was false')

else:

print('condition_1 was true')Testing and:

at least one part is false

Testing or:

at least one part is true

Testing not:

condition_1 was trueJust like with arithmetic, you can and should use parentheses whenever there is possible ambiguity. A good general rule is to always use parentheses when mixing and and or in the same condition.

Challenge 5

Before we move on from our foray into boolean logic, let us make a brief mention of the &, |, and ~ symbols. These are similar, but not identical, to and, or and not. Where and is used for boolean logic on scalars, & is used for boolean logic on vectors, and will do an element-by-element comparison. This will be important when we introduce data structures later on!

3.4 Methods & Chaining

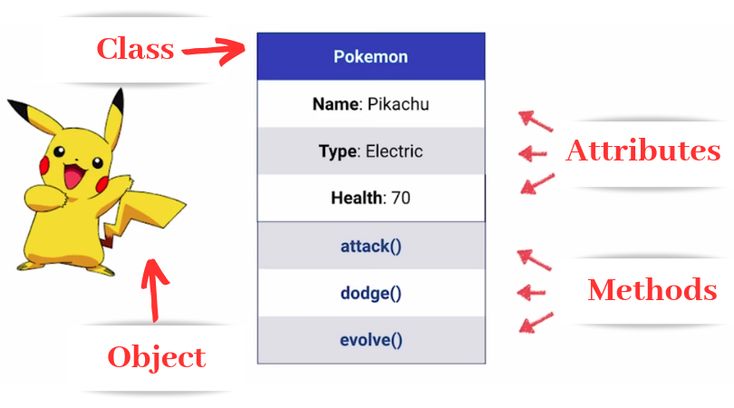

Object Oriented Programming

So far we have seen built in functions that can be applied to a variety of different datatypes (as long as the datatype makes sense for that particular function). However, there are some functions that we apply specifically to a particular class of objects - we call these functions methods. Methods have parentheses, just like functions, but they come after the variable to denote that the method belongs to this particular object.

We have met classes already: all of our basic datatypes (strings, integers, floats, booleans) are different classes of objects in Python. An individual instance of a class is considered an object of that class. Understanding how to use methods will become useful when we reach the pandas portion of the course, which is our main tool when looking at, cleaning, and summarizing data.

Let’s consider the string class. Here are a few common methods associated with it:

lower(): coverts all characters in the string to lowercaseupper(): converts all characters in the string to uppercaseindex(): returns the position of the first occurrence of a substring in a stringrjust(): right aligns the string according to the width specifiedisnumeric(): returnsTrueif all characters are numericreplace(): replaces all occurrences of a substring with another substring

You will notice that trying to find help on a method will not work if you only specify the method. Because these are not built in functions, and only belong to instances of a class, you need to specify the object together with the method to use help.

For example, help(lower) will result in an error, whereas help("any string".lower) will give you the help you were looking for.

Let’s see some of these in action. You’ll notice that when being used, methods don’t always have an argument supplied to them. That is because the first argument is always the object is being applied to. If a method requires secondary arguments, these are subsequently included in the parentheses.

object.method(a, b, c, ...) ↔︎ method(object, a, b, c, ...)

my_string = 'Peter Piper Picked a Peck of Pickled Peppers'

print(my_string.lower())

print(my_string.isnumeric())peter piper picked a peck of pickled peppers

FalseWe can also chain methods together. Each subsequent method (reading from left to right) acts on the output of the previous method. Chaining can be done in a single line, or over multiple lines (which helps for readability).

print(my_string.upper().replace('P', 'M'))

# Chaining over multiple lines can be done in 2 ways:

# 1. Enclose the entire operation in brackets

chain_1 = (my_string

.upper()

.replace('P', 'M')

)

# 2. Use the character "\" to denote an operation is continuing on the next line

chain_2 = my_string \

.upper() \

.replace('P', 'M')

print(chain_1)

print(chain_2)METER MIMER MICKED A MECK OF MICKLED MEMMERS

METER MIMER MICKED A MECK OF MICKLED MEMMERS

METER MIMER MICKED A MECK OF MICKLED MEMMERSChallenge 6

Challenge 7

3.5 Accessing Other Packages

Import Packages

Most of the power of Python lies in its ability to use libraries, or external packages that are not part of the base Python programming language. These libraries have been written and maintained by other members of the Python community, and will make data cleaning, manipulation, visualization and any other data project much simpler. Throughout this course we will use packages such as:

pandas: this is the go-to package for all things data-table.matplotlib: this is the most frequently used plotting package in Pythonseaborn: this is a plotting package built with pandas and data in mind

When we set up our Python environment, we already installed many of the packages we will need directly into the conda environment we produced. If you ever need another package, it is simple enough to install again using conda:

Anaconda Prompt

> conda activate ds-env

> conda install <package>If you are ever searching for a package you think will aid you in your work, you might come across the pip command. This is a different (yet related) method of installing packages. While it is possible to use pip in tandem with conda commands, it is recommended that you stick to only conda wherever possible.

As a rule of thumb, try to conda install package as a first try. If this does not work, search the website for the package for installation instructions. Sometimes it will recommend using a different conda channel (and will provide the code to do so). Sometimes, it is only possible to get the package from pip, in which case using pip inside the conda environment is the only way to go. Just use this as a last resort!

Okay great, we have all these awesome libraries that have been built out by others. How do we actually use them? In Python, it is actually fairly simple!

Option 1: Use import to load an entire library module into a program’s memory. Refer to things from the module as module_name.thing_name

import math

print('pi is', math.pi)

print('cos(pi) is', math.cos(math.pi))pi is 3.141592653589793

cos(pi) is -1.0Option 2: If we only need a specific function or tool from the library, use from module import thing

from math import cos, pi

print('cos(pi) is', cos(pi))cos(pi) is -1.0Option 3: If we really do need the entire library, but we do not want to type the entire long name over and over, create an alias

import math as m

print('cos(pi) is', m.cos(m.pi))cos(pi) is -1.0Some common alias for common libraries include:

pandas→pdmatplotlib.pyplot→pltseaborn→snsnumpy→np